Adventures in Scotch Land

Step into a bog anywhere on Islay and the source of the smoky flavor synonymous with the whisky of this westerly island of Scotland begins to sink in—just as soon as your foot begins to sink into the spongy, peaty turf. Plants decomposed for 10,000 years under the grassy surface create a handy fuel with which to dry the barley that forms the granular heart of a single malt. Turned into liquid, it still tastes of its bath in the bog's smoke. Now board a boat and view Islay from the sea. Looking in at the coast where warehouses for Laphroaig, Lagavulin and Ardbeg line up a few feet from the waves and you'll likewise understand whence their salt and iodine tasting notes arise. Surf batters the shore, churning up briny water and seaweed into the air the sleeping whisky breathes.

You don't have to be a spirits chemist to figure out how the land and the sea shape the whisky that flows from Islay.

Wine makers call this terroir—that special relationship between place and product that can explain why the same grape variety grown in the same way in two places can taste so different. In Scotland, a hundred distilleries dot the map, each making unique whiskies that speak—in a shout or a whisper—of the diverse locations in which they are made.

For this reason, it is popular to divide the country into a number of whisky-making regions with a view to categorizing tastes. This may be handy, but it's a little too convenient to describe the country with the most diverse whisky styles in the world. Too many other factors go into production and too many contradictions exist for such a mysterious and irascible land as Scotland to be so neatly labeled.

It is easy to say that Islay whiskies are bold and smoky, Speysides are sweet and fruity, Lowlands delicate and floral, and for the most part you'd be right. But what of the huge Highlands area? It is widely spread out and includes a number of malts that are hard to reconcile stylistically. What some call the Islands region is an easy way to cordon off the Highland distilleries that are not on the mainland, but those islands are far flung and once again bridle at conformity. The Scotch Whisky Association, for purposes of labeling, recognizes five regions: Highland, Lowland, Speyside, Islay and Campbeltown, but that last designation isn't very useful as it refers to only three distilleries in a very small area. More industrious labelers have divided the Highlands into East, West, Central and North and separated the islands into Arran, Jura, Mull, Skye and Orkney. But then that's a lot to process, if the point is to simplify Scotch.

So how do you come to with Scotland's whisky diversity? Happily, the great majority of the country's distilleries welcome visitors and are very proud to explain what sets their products apart from others. Short of a Caledonian tour, you can also explore by reading on or, perhaps in happier manner, by further tasting.

Far north and east of Islay in the Highlands town of Tain near the North Sea, the Glenmorangie master blender and whisky creator Rachel Barrie leads a tasting of the wide range of whiskies she helps create. She starts by pointing out that only three things go into Scotch malt whisky—water, barley and yeast. It doesn't take long to catch on to her irony. Not only is her fruity and oaky whisky markedly different than that of most Islay whiskies, the expressions she offers—the original, Sonalta, Quinta Ruban—vary from glass to glass even though they were born of the same still.

To understand why, you must look not only to the variations that are allowed within Barrie's terse summation of the formula, but also to other variables it doesn't include.

FOLLOW THE WATER

|

The first factor to consider with Scotch whisky is water. Every distillery has an enormous thirst and is typically built close to a generous source that has been determined to yield the best water for its job. It is supposed that when the John and Tommy Dewar built their Aberfeldy distillery to supply their famous blended whisky, they choose the location because of its proximity to their father's birthplace. Nostalgia notwithstanding, the savvy brothers would not have picked the location, if the Pitilie Burn, high above it, hadn't already proved to be an excellent water source for a distillery that had formerly operated nearby.

The Speyside region offered two advantages to the early distillers that first crowded its hills and mountains centuries ago: haven from the authorities (most were moonshiners in the early days) and the numerous springs that feed the River Spey. While they might have moved closer to the city when taxes eased enough to make it profitable to operate in the open, the stillmen stayed for the felicitous water sources.

The terroir of many Scotches may best be defined by water. Glenmorangie's source is Tarlogie Springs, a short distance from the still house. It's not much to look at—a shallow pond perhaps 30 feet by 30 feet—but you can see by its sandy bottom that the clear water, which takes a hundred years to bubble up, has filtered through sandstone and limestone. Back in Islay, Laphroaig uses water that flows over the heather of granite hills and runs through all that peat in the bogs. Each has its own effect on the whisky.

Yet the differences in water sources are not only particular to large areas, but a sort of microgeology particular to each maker. Looked at through H2O, almost every still—even when built next to another—is its own region with its own personality.

While Speyside isn't thought of as making peaty whisky, quite a bit of the stuff is in the soil, Cardhu, one of the least smoky of whiskies, takes much of its water from springs in the nearby peat-filled Mannoch Hill. Nevertheless, The Glenlivet, not far from Cardhu, prides itself on the mineral-rich water it takes from Josie's Well.

Water has many functions in the whisky-making process. It first s in when barley is steeped to begin the malting process that coaxes sugar from the grain. Then it is added in mashing, prior to fermenting a crude beer. It is in these stages that water quality is thought to have the greatest effect, as it interacts with the grain and yeast.

Water is further needed during distillation. This step captures high-proof spirits by essentially boiling alcohol out of the beer and then condensing it back into liquid form. Some whisky men feel that the temperature of the water used to cool the steaming spirit has a distinct effect on taste. If this is true, the cold waters of such high-altitude distilleries as Dalwhinnie and Tomatin would have a dramatically different influence than those at the distilleries closer to sea level.

|

When whisky comes out of the cask years later, it is typically far above 100 proof (half alcohol) and water is once more used to dilute it to bottle strength (which can be as low as 80 proof, or 40 percent alcohol). This water can be a moot point in the terroir debate, however. That is because it has been typically distilled for neutral taste and usually doesn't share the geography of the rest of the liquid as few distillers bottle on site.

GOING WITH THE GRAIN

In wine, terroir is largely a function of organic content, when the grapes used to make the juice are grown in the same place as the winery. This is hardly so in Scotland, where very little of the barley in a whisky is likely to be grown in the area where the spirit is produced. Regulations don't even stipulate that the grain content come from Scotland, although much is grown in its coastal areas. (Other popular barley sources are England, Scandinavia and Africa.) Some distilleries buy a portion of their grain from nearby farmers or have their own plots, but the volume of barley necessary usually precludes a 100 percent single-estate approach to grain.

The recent thrust has been to buy barley within Scotland, but the impetus behind that has been mostly economic rather than terroir-driven. (Shipping costs are prohibitive for foreign barleys.) Barley purchases tend to be pragmatic—the yield of alcohol-to-grain is the foremost determinant. But even while new varieties of barley are constantly being developed with names like Optic, Tankard and Chariot, Macallan highly prizes the less alcohol-efficient Golden Promise, a strain that has been used since the 1960s. However, it has had to add other strains of barley to have enough to meet demands.

A notable exception to the practice of mixing barley varieties is 1991 Triumph in The Glenlivet Nadurra line. As well as being a vintage whisky from that year, it was made wholly with Triumph barley. Moreover Glenlivet no longer uses that type of barley, so don't expect to see much of that.

THE FOURTH INGREDIENT

"It's just like butter, guys." Laphroaig distillery manager John Campbell is demonstrating how to harvest a fourth ingredient in most Scotch whisky, one that isn't covered in the aforementioned water-barley-yeast formula.

He sticks a peat spade, a narrow tool with a flat end and a wing protruding from it on the perpendicular, and cuts into the soft soil to extract an almost perfect brick of peat, the partly decayed vegetable matter found beneath much of Scottish land. Piled in the stacks that are not uncommon sights in Scotland, these peat bricks dry out enough to burn, but are moist enough to provide the smoky taste that is—in varying degrees—the signature flavor note of the nation's spirit.

By sheer volume, peat is almost not worth mentioning—it is measured in the parts per million phenol. Far less than a drop exists in a bottle of even the peatiest of whiskies. But it is this minute ingredient that makes Scotch whisky instantly recognizable. Yet the peat smoke that laces most single malts wasn't originally meant solely for taste. When water is added to barley, it begins to germinate, releasing the sugars that the yeast will later feast on. The sprouting must be stopped ("John Barleycorn must die") before the sugars can be turned to alcohol during fermentation. Drying the grain stops the germination, and because peat is so common in Scotland, it was the preferred fuel for doing the drying job in the days when coal heat was a luxury.

No law compels Scotch whisky makers to dry barley with peat smoke (in fact Glengoyne and Auchentoshan don't use it all), but the tradition has ed down simply because it brings so much flavor to a malt. That the style of Islay malts is particularly peaty is probably tied to the abundance of peat there. But while some of the island's malts—Laphroaig, Ardbeg, Lagavulin—lead the league in smoke content, Bunnahabhain and Bruichladdich eschew that profile and the normally peaty Caol Ila also makes an unpeated version. Those contradictions exemplify how aspects that are often considered part of the Scotch terroir are simply regional styles that are not chiseled in stone—or peat in this case.

Nevertheless, a peat terroir does exist as the waterlogged vegetable matter has a different chemical makeup depending upon where it is decomposing. Islay's peat is high in lignum. At Orkney's Highland Park, the northernmost distillery, the peat has more carbohydrates.

Nowadays most barley reaches the whisky plant having already been peated to order at a malting plant. Laphroaig controls its own peat content (which is very high, about 50 parts per million) first by cutting the peat by hand, which retains moisture and makes the fuel burn smokier.

Secondly, it performs its own floor maltings, which is the old-fashioned method that only a handful of distilleries, such as Balvenie, Highland Park and Glenfiddich, have retained. Most of the eight Islay distilleries are supplied with barley by Port Ellen Maltings, a former distillery now devoted to germinating barley and drying it in large drums.

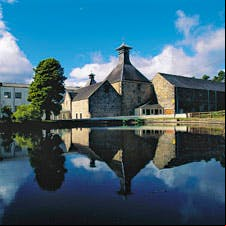

At Laphroaig, the barley is spread out and wetted down across concrete floors. For days workers turn the barley by hand as sprouts appear on each corn and grow to the correct length. It is then that the workers fire peat ovens, and smoke wafts up to dry the grain and stop the germination. While pagoda roofs are common on Scotch distilleries, on most they are mere vestiges of a time when they peated their own barley. In the case of Laphroaig, the spire still shrouds a chimney used for expelling peat smoke.

After the germination is halted, the barley is ready to be milled and mashed—ground into grist and mixed with hot water, creating what is known as wort. Yeast is added and the wort is put in washbacks, huge open vats with capacities of tens of thousands of liters. There it ferments for several days, turning into noncarbonated beer.

STILL STANDING

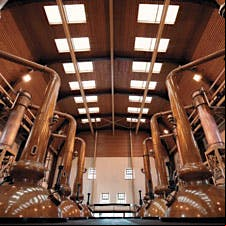

The beer then enters another microclimate unique to each distillery—the still. Every distillery uses a different shape and sized still. Some use two different types for the first run (wash still) and the second (spirit still).

It is in the distillation of Scotch that size—in particular height—matters. Glenmorangie has the tallest still, letting only the lightest spirits escape. Macallan's are among the smallest, which concentrates the flavor of a spirit meant for long aging. Aberfeldy's are large and bulbous, which renders the light, honeyed malt that informs the Dewar's blend. So important are still dimensions that when The Glenlivet recently expanded, pains were taken to replicate the exact shape (tall and wide) of its stills.

Work on the pot stills of Scotland create enough business that outfits like R.G. Abercrombie coppersmith are devoted to these tasks. In its Alloa facility, parts of stills are being worked on, cut in basic form and forced into shape with hammers. The smiths all wear serious ear protection from the constant din as they attend to mushroom- and onion-shaped stills from makers such as Oban and Talisker.

Copper has charms that improve the taste of whisky as it interacts with the metal. If this were true of stainless steel, Abercrombie would have much less work. But copper wears out over 10 or 15 years-seldom at the same rate-so most of the work is piecemeal maintenance. Rarely are the smiths called upon to create an entire still at once, as Abercrombie was when Diageo opened Roseisle, the first new distillery in Scotland in 30 years. Then the coppersmiths had the opportunity to construct 14 stills in one fell swoop.

Back in the still house, the first run creates what are called low wines, bringing the alcohol content to about 20 percent before the second finishes the job, resulting in a spirit of between 60 and 75 percent alcohol. In the Lowlands region, as with Irish whiskey, a triple distillation employing a middle still has been traditional, but is now only used at Auchentoshan.

|

It is in the last run that distillation style is typically distinguished. The overall run of the still is diverted, or cut, twice. The foreshots that begin the run are sent off because they contain impurities. Then at some point before the end of the run they further divert impurities called feints. The foreshots and feints are retained, however, and redistilled in a later run.

The point at which the spirit is kept for aging and, later, to be bottled, affects the final product quite profoundly and each distillery has philosophy for when to do this. Some amount of impurities are actually desirable because when aged they contribute to a whisky's character. If the desire was to eliminate impurities completely, they would use industrial column stills, like vodka makers do, instead of old-fashioned pot stills.

The fresh spirit is now ready for aging: the longest and arguably most important part of whisky making. As Cardhu's Duncan Tait, an operations manager, points out, his part of the process is to create new-make spirit, which takes only about 95 hours. The next leg of the journey will last 12 years and that it is when single malts truly become whiskies.

As romantic as it to think of maturation as an integral part of Scotch terroir, enthusiasts may be surprised to learn that aging doesn't necessarily take place where the spirit was created. Often the space and complex cask management requirements for large scale whisky-making make the efficiencies of aging elsewhere more compelling than the charm of aging on site at the distillery. First of all, not every location confers the same local flavor on an aging cask as will Islay with its wind-and-saltwater-whipped shores.

Second, the vast majority of single malt is destined to become part of a blend. The management of the several million required casks is sometimes better done at a series of warehouses. Some are designed to handle whisky for blends, others are traditional single malt facilities.

Aging undoubtedly has the most influence on a whisky, but as well as the "where at," it is the "what in" and the "how long" that makes the difference. Nowadays Scotch whiskies are distinguishing themselves foremost through the quality and of types of wooden casks used for maturation. That process begins outside of Scotland, usually in the United States.

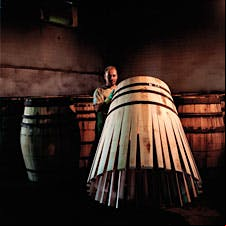

Because by law Bourbon makers can use their new oak barrels only once, Kentucky and Tennessee are steady sources of relatively inexpensive casks as they sell off used stock. Disassembled barrels are shipped to Scotland, where they are reassembled and used again, sometimes over and over. The first-fill casks confer the most flavor on Scotch. At certain point the casks are spent and either discarded or used for neutral storage, as in marrying whiskies in a blends. Some Scotch makers, such as Balvenie, employ their own coopers to work on the wood. Much is done at places like Carsebridge Cooperage, where barrels are piled in small hills destined to be shipped to Scotch warehouses.

Inside there is a faint smell of Bourbon from all of the wrapped staves.

Reconstruction not only means assembly of barrels, but sometimes cutting staves to create casks of different sizes to fit the needs of the distillers they are destined for. The cooperage also rejuvenates barrels that have already been used in Scotch making, scraping the insides to get to fresh layers of wood and then charring them so the whisky can more easily take the flavor from the wood.

Some 80 percent of Scotch whisky is matured in American wood. Sherry and Port vessels make up most of the rest, and Scotch makers have long-mixed whisky aged in different wood types. The Glenlivet has brought together whiskies aged in American oak as well as French Limousin oak. Even the Macallan, which once exclusively used Sherry wood, now has a program to ix whisky aged in American-oak.

Novel ways to store whisky are appearing all the time. A development of recent decades is called finishing, in which a Bourbon-aged whiskey spends several months in another cask. This is a particular specialty of Glenmorangie, which has finished whiskies in various Sherry and Port casks, even Sauternes vessels. Recently, Balvenie, a distillery known for lightly peated malts, released a whisky that enjoys a finish in barrels once used to age heavily peated whiskey. Com Box, a whisky negotiant, has a blended malt that it finishes in barrels made of both American and French oak.

|

Macallan is perhaps the leader in wood management, having begun to order casks made to their specifications from European, and now American, oak that is then seasoned with Sherry in Spain. For the brand, which had once been very much aimed toward the blend market, it has meant concentrating more and more on its single-malt presence. And it's been rewarding, as it continues to gain accolades.

Super age is another important direction as exemplified by the record prices that malts of 35 years and older, especially The Macallan, The Dalmore, Glenfiddich and Bowmore, continue to garner in the auction market. Two years ago, New York State allowed the first auctions of spirits since Prohibition and that avenue for purchasing whisky has burgeoned ever since. Great age is not limited to special releases, however, and brands like The Dalmore, Glenfiddich and Macallan have 50- and 60-year-old malts in their permanent offerings. Even blends like Famous Grouse 30-Year-Old and Royal Salute 38-year-old Stone of Destiny are expanding the age envelope.

The Glenrothes and The Glenlivet have vintage programs that stretch back four and five decades, with malts that were distilled in specific years. With wine a vintage generally shows off the quality of a grape crop that's been grown in a specific year. Whisky's grain doesn't change much from year to year, and vintage is more about the subsequent years spent in casks. (Bottle time does not contribute to age.) A vintage Scotch would be a sort of record of casks that had shared the same climatic conditions over their maturation. (When you buy a bottle identified by age—say 12 years old—it doesn't mean that all the whisky is from the same vintage, just that it is a minimum of that age. Casks of 13 years or more may have been, and probably were, used to make the vat it is bottled from.)

And yet, it is likewise too convenient to lay Scotch whiskies taste to aging or stills or barley or water, all the things you can easily tabulate. With Scotland, there are always mysteries. Back in Cardhu, a distiller who has just reintroduced its whisky to the American market after years of not having enough product to meet a surging demand, Tait says of the problem: "We can't make anymore here and we can't do it somewhere else. If we could we would. Marketers are eternal optimists and if we were to produce to what they want we would have lakes of whisky."