Stalking the Tiger

It's late on Friday afternoon at the 2006 Ford Championship in Miami and the Doral Blue Monster course is abuzz. Tiger Woods is out there, but it's not about him. Phil Mickelson is playing, too, but it's not about him. It's not about Ernie Els or Sergio Garcia or Vijay Singh.

Eddie Carbone, the executive tournament director, knew what the buzz was about. He had been sensing it for weeks. He had gotten e-mails and phone calls asking if a certain player would be in the field. He and his staff had been assuring people that, yes, this player would definitely be teeing it up. As Carbone stood outside the tournament office on Friday afternoon, a thunderous roar rolled across the Blue Monster. Carbone knew it wasn't for Tiger or Phil or Ernie or Sergio or Vijay.

He knew it could be for only one player: Camilo. Camilo? Yes, Camilo. Camilo Villegas. The newest, hottest player on the PGA Tour.

"He's going to be an international superstar," says Carbone, who's seen a lot of superstars. "He's going to reach out to the Spanish-speaking people around the world. Everybody's going to know who this kid is. He's special."

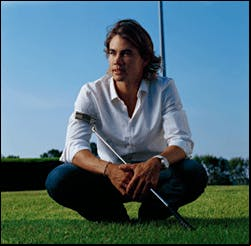

The sunlight will be fading soon in the atrium of a Houston airport hotel. A photographer is arranging a photo shoot of Villegas to catch the optimum light on his caramel skin and his glowing long tresses. Five young women in their early 20s by, most likely on their way to a workout room or a jog. They see Villegas changing shirts, his sculpted upper torso rippling, and they can't take their eyes off him. They have no idea who he is. They have no idea that he is the best golfer from Colombia, a country known for coffee and Pulitzer Prize—winning author Gabriel Garcia Marquez, but other, less savory products, too. They have no idea that he was a four-time All-American player at the University of Florida. They have no idea that he is off to a brilliant start on his rookie year on the PGA Tour. They do know, however, that he has something special, because they are staring at him with twisted necks even as they go out the door. They know he has "it."

What is this "it?" As a PGA Tour player, Villegas has power, touch, focus and imagination. As a personality, he has looks, smarts, grace and magnetism. People come to watch him play golf. People come to watch him be Camilo.

"His impact on our tournament was sensational," says Carbone. "I had people from Colombia e-mailing, calling, wanting to make sure that he was in the field because they wanted to come up from Colombia to watch him play. We have such an extensive Latin community in Miami. Of course, we have a large Cuban population, but lots of people from South America, too. Colombians, Venezuelans, Brazilians. They caught wind of this kid. It was incredible."

Villegas caught lightning in a bottle the final day of the Ford Championship. Playing before an enormous and ionate gallery made up largely of Latinos, Villegas was pressing leader Tiger Woods before an errant drive and three putts at the 18th led to a double bogey and a tie for second place. That he did not win the tournament meant little. That he did win such a huge following meant everything.

"I told my caddie standing on the 18th green that it was the most awesome week I ever had," says Villegas, relaxed and confident on a hotel couch in his J. Lindeberg shirt and his J. Lindeberg jeans. "Playing good golf at the right place at the right time in front of the right people. I don't have any idea how many people out there had no clue as to what is a par, birdie, putting green. It was golf with a soccer crowd. You could see all the Colombian flags. People yelling and screaming for me. So I clapped my hands for them."

Johan Lindeberg saw the "it" in Camilo Villegas nearly three years ago as he was surfing the Internet. Lindeberg, the creative director of the Swedish fashion company J. Lindeberg and a ionate golfer, came across Villegas as a college player at the University of Florida, and from those first Internet pictures he thought he discerned a quality about him that was undeniably attractive. Two years later, when he met Villegas after he had turned pro, when his company had him under contract to wear his golf clothing and the rest of his collection, Lindeberg knew he was right.

"I am always studying golf and I thought he was the best-looking golfer ever," says Lindeberg. "His arms, his eyes, his looks. To me, he was the new Marlon Brando. He has that intensity of charisma, of strength, that Brando persona. To me, he has the most unique look as a golfer since Arnold Palmer. Tiger Woods operates on a completely different level in the world, no doubt. But Camilo has tremendous international appeal."

So, is Camilo Villegas the next Tiger Woods or the next Marlon Brando? Does he have 10 major championships in his game, does he have a remake of On the Waterfront in his future? Tough acts to follow, to be sure. But be sure of one thing: Villegas wants to make his own place in the world of golf and he seems to have the tools—the body and the brain—to make very good things happen. Through this past April he had finished second twice and made an extremely impressive third-place showing in the Players Championship. He had won more than $1.2 million, already ensuring that he would finish in the top 125 on the money list and hold his PGA Tour card for 2007.

Now comes the true test, whether Villegas can become a winner on the PGA Tour, whether he can become an elite player, whether he can become a contender for the crown currently held by Woods and once held by Palmer and Jack Nicklaus. Most players are pretenders to that kingdom. Sergio Garcia is a winner, but not a major winner. Greg Norman, for all the expectation and excitement that swirled around his career, never quite wore the royal robes despite winning two British Opens. Villegas has a ways to go on results, even if he is just arriving as a personality.

The journey of 24-year-old Camilo Villegas to the PGA Tour began in the unlikely city of Medellín, Colombia. The son of architects Fernando and Luz Marina Villegas, the young boy was attracted to the popular sports of the country—soccer, biking and squash. His father had been a well-rounded athlete who played soccer and tennis and rode motorcycles competitively. At 35, Fernando decided to take up golf and ed Campestre de Medellín, one of four clubs with golf courses in the city of nearly two million in the northwest part of the country. Medellín is known as the Land of the Eternal Spring and the Capital of Flowers and is a principal manufacturing center. But it is also widely known as the center of the Colombia drug cartels. That is a reputation that Villegas would like to erase through the game of golf.

"If I play good golf and people say, 'Hey, he's from Colombia and he's doing something positive,' I think that will help with what people think of Colombia…. It's a pretty country with people who are ionate and will make you feel at home."

When Camilo was seven, Fernando took his son to the Campestre de Medellín. The boy hit a few balls, then a few more, and soon knew that he had found the sport he wanted to play. "Soccer was not a sport I really loved," says Villegas. "I really enjoyed biking and I liked playing squash. But I really loved golf. Golf was the one that I really wanted to do better, the one I worked the hardest on, the one I had the most ion about. There was something about it I really enjoyed. I knew golf was the one I wanted to do special things with."

Under the tutelage of the club pro, Rogelio Gonzalez, and the of the Federación Colombiana de Golf, Villegas became one of the country's best players by the age of 13. "One of the best things about playing golf in Colombia is that if you are a good one, you get a lot of opportunities to represent your country," says Villegas. "Being the third best player in Colombia is a lot easier than being the third best player in the United States. So if you are third best you get a lot of opportunities." His résumé included two South American junior championships, a victory at the Colombian Open as an amateur and three appearances in the World Amateur.

Villegas was doing special things without the benefit of a world-renowned swing coach, a sports psychologist or a personal trainer. At an early age he was focused and mature. His parents never pushed him to play golf, nor did they push him to open a schoolbook. But they did tell him that whatever he was doing, he should dedicate himself to it and give it his best. He has made that advice his credo and it is at the center of his present success. In that regard, he could be the equivalent of Tiger Woods, whose late father, Earl, and mother, Kultida, took a similar approach in raising their son.

As Woods was starting his fourth season on the PGA Tour in 1999, Villegas was coming to America and making a lasting impression. He finished fifth in the World Junior Championships in San Diego, lost in the final of the U.S. Junior Amateur Championship in York, Pennsylvania, to Hunter Mahan (now a fellow PGA Tour player) and won the Orange Bowl tournament in Coral Gables, Florida. The U.S. Junior is a key tournament in the college recruiting rotation. Among the more than 80 college coaches there that year was Buddy Alexander, leader of the University of Florida's highly successful golf program. Alexander already had a Colombian player on his team, Camilo Benedetti, who had gone to high school in Fort Lauderdale his sophomore year as an exchange student. Now Alexander and a legion of coaches were watching Villegas establish himself as a blue-chip prospect. "Let's say he drove up the price by his performance there [at the Juniors]," says the Florida coach.

The University of Florida is where Villegas wanted to go. With Benedetti already at the school, with Alexander as one of the premier college coaches, with the team highly competitive on a national basis, Villegas set his heart on becoming a Gator. He was going to play with the best, and he was going to get a degree. As much as he loved golf, he also knew there were no guarantees that a rich professional career was in his future.

"If I had stayed in Colombia, it was going to have to be golf or it was going to have to be academics," says Villegas. "Coming to the States, it was nice to be able to combine both, something I always wanted. Golf is a tough sport; there are so many good competitors out there, so you never know what can happen. I have a ion for the sport, but I had to have a backup in case it didn't work out. So I had to get my degree." (Villegas would major in business istration, graduating with a 3.78 GPA.)

The player that Buddy Alexander had recruited had a game based on finesse and strategy. The 5-foot-9, 139-pound freshman was one of the smallest players on the team in 2000, one of the shortest off the tee. Villegas wanted to change all that and so did Alexander. "He didn't really generate enough clubhead speed," says Alexander. "We put him on a program to make him stronger. Lifting weights, nutrition. He took it to a level that no had ever done before."

|

Eventually, Villegas would get up to 160 pounds of lithe, rippling muscle, enough to propel him into the top 10 in driving distance on the PGA Tour. He would win eight tournaments in college, breaking the school's record held by PGA Tour player Chris DiMarco. His first two years, he was a first-team All-American. He won two tournaments his junior year, but somehow was voted only to the third team. He returned to the first team his senior year in 2004. It was sometime during his sophomore year that he started thinking that a professional golf career might be possible. He was hitting the ball far, sometimes farther than anyone else on the team. His putting and his wedge games were improving He was a consummate practice-range rat who found his success, as they say, in the dirt (and in the weight room). "He is as disciplined and dedicated a player as I've ever had," says Alexander. "He does things the way you can only hope to teach them."

NBC television analyst and former Gator Gary Koch closely watched Villegas's progress. "I played with him on Gator Golf Day when he was a freshman and he really was a skinny little kid," says Koch. "But you could just sense there was a presence about him, the way he carried himself. He was very polite and it was obvious that he was brought up very well. You just thought he had to do some great things."

When Villegas left Florida in 2004, he turned pro. IMG, the mega-sports agency that built its reputation on Arnold Palmer and represents Woods and many of the world's leading players, had been first in line for several years to sign him up. The minders at IMG knew that Villegas—like Palmer and Woods before him—had that "it" factor, a charisma quotient that transcended the game. "We like to have people who are a little different," says IMG senior vice president Clarke Jones. "Right when you meet him you realize he's got something. You realize how organized and dedicated he is. He was a great student, very diligent, very mature. And he's got that Latin flair."

His first big professional event was the U.S. Open at Shinnecock Hills in 2004. Villegas had gone through two stages of qualifying to earn his spot. College golf is played on a very high level, but generally in front of more trees than spectators. Now Villegas was getting to see what the big time was all about, and it agreed with him. "I missed the cut, but it gave me a taste for the life out there," says Villegas. "It showed me I could play golf in front of people, put on a show, and I like that people were having fun with it. It made all the hard work I had put in worth it."

Through IMG's stumping and Villegas's accomplishments, and through his growing "it" factor, he was able to get sponsor invitations into seven PGA Tour events in 2004, the maximum allowed to any player. When he finished in a tie for seventh at the B.C. Open, that allowed him to play the next week. Altogether he played in 10 PGA events that season. But because it's almost impossible to win enough money in such a few number of events, it's difficult to gain top-125 money-list status, which guarantees a spot on the Tour for the following season.

Because he was not a Tour member, Villegas did not gain an entry to the Nationwide Tour—golf's top level below the PGA Tour—for the following year. He had to go through the full three stages of Tour qualifying to get a card. At the second stage, he missed. At that point he had no status anywhere, though being an IMG client conveys status in its own right. It helped him get into events on the Australasian Tour at the end of 2004; he finished in the top 60 on that money list, enough to gain tour status there. He had a home base, if he needed it.

"In 2005, I knew I was going to get some sponsors exemptions into PGA Tour and Nationwide Tour events," says Villegas. "I got a sponsor exemption into the first Nationwide Tour event of the season in Panama and finished second. I thought to myself, This is going to be a good way to get onto the PGA Tour." (The top 20 money winners on the Nationwide Tour, plus ties, gain provisional status to the PGA Tour. Villegas finished 13th.)

One of the sponsor exemptions that Villegas received in 2005 was to the Ford Championship at Doral. Eddie Carbone had been aware of Villegas's achievements at the University of Florida. He saw that "it" something in Villegas and had him play on the media day for the Ford Championship that January. "You could really tell that this kid had something special," says Carbone. "He's the most gracious and personable guy. I loved the way he interacted with everyone. He has a good appreciation of what it takes to be a complete pro, how he needs to interact with the sponsors and the fans."

Carbone was saving another sponsor exemption for Villegas to the 2006 tournament. The Ford Championship is one of the Tour's most prestigious events and most of the top players compete. Players like Villegas whose status come from the Nationwide Tour money list are often left out. Then Villegas hit the jackpot. He finished in a tie for second at the FBR Open in Scottsdale, Arizona. The $312,000 he won zoomed him up the money list and guaranteed him entry into at least the next few big events, the Ford Championship included. He was on his way to national, and international, exposure.

The "it" man had arrived.

"Johan had been telling me about him for a couple of years," says PGA Tour player Jesper Parnevik, who was the first significant player to wear Lindeberg's golf clothing. "He kept saying, Watch out for this guy. He said he was so photogenic that it's unbelievable. He kept calling him a young Marlon Brando, which was pretty unusual to be calling a golfer that. But Johan has a good sense about these things."

Lindeberg also had a good sense about Villegas's ability. He thought he would be a Tour winner, and Parnevik sees nothing about Villegas's game to think differently. "He's a young kid but he thinks like an experienced player," says Parnevik. "At Doral he missed some short putts, but he did not come away disgusted. He keeps the positive and throws away the negative. To me, he is a modern Seve [Ballesteros]," adds Parnevik, referring to the charismatic Spaniard who won three British Open and two Masters titles.

Villegas, however, hasn't always been upbeat about his game.

"Controlling his emotions is something that Camilo has had to work at," says Alexander. "He's never been a hothead or a club thrower, but he can get upset enough at himself that it could be detrimental. He's a perfectionist, which can be good and it can be bad. He could beat himself up pretty good. My parting words to him were not to get down on himself."

As with so many pros, putting gets Villegas down. Last year, he literally started getting down in an effort to improve that aspect of his game. At the Ford Championship this year, the gallery and the television viewers were introduced to Villegas's acrobatic method of reading putts, balancing himself on one leg, then getting down so low to the putting surface that it looks as if he's lining up a billiard shot. If Fred Couples tried to do that, it would take a crane to hoist him back up. "It was just another way of giving myself a better chance to make putts, to see the line more perfectly," Villegas says about the praying mantis technique.

But perfection has its price. Villegas has always been a perfectionist. His yardage books, drawn to scale, are works of art. He numbers his athletic socks to match up the same pairs every time he washes them. He is fastidious with all of his clothing and keeps a very clean apartment (he has moved into a new home in Gainesville, Florida, which he shares with brother Manuel, a redshirted junior at Florida). "Last year I had a bad year with putting," says Villegas. "I worked a lot on my mechanics. I worked at the Titleist facility in California. I got a lot better, but I was not making putts, and I was getting frustrated. I tried to be more perfect, more perfect, more perfect, and that was going the wrong way. This year, I finish second at FBR and I feel bad over every putt."

So he called Gio Valiante, a sports psychologist who is also a volunteer assistant coach with the Florida golf team. "My mind was not working the right way. I was too concerned about reading the putt perfect, aiming the putt perfect and making a perfect mechanical stroke. He said, Think about shooting a basketball. You just look at the rim and shoot. He said, You are a great athlete, you've been doing this your whole life, don't make it harder on yourself. Look at the cup and hit it. He called it 'Caveman Golf,' going back to when you were a little kid and just looked at the hole and hit it."

The approach worked. After he finished in a tie for second at Doral, Villegas tied for third at the Players Championship against the best field in the game. He had not been guaranteed a spot in the Players field at the start of the week, then fellow Gator Chris DiMarco pulled out after injuring himself skiing. Had Villegas made one more putt and finished alone in third, he would have put himself into the Masters by being in the top 10 on the money list at that time.

"Everybody kept asking me, Are you going to get into [The Players], are you going to get into the Masters, are you going to get into the U.S. Open?" says Villegas. "I don't care. I do care, but I don't want to know it. I do want to play in the U.S. Open and I do want to play in the Masters. But I can't control numbers out there, I can't control what other guys are doing. I can only control myself."

That there are some things he can't control is all right. The spontaneous eruptions of the huge galleries that followed him at Doral, the women, young and old, who press against the ropes and call his name, the men in hotel lobbies who ask how he's going to do this week. They are all attracted to the aura he has generated through his game, through his persona. This is all good, he knows, as long as he keeps one thought in mind.

"It's all about playing good golf," says Villegas, the "it" man of the moment.

Jeff Williams is a Cigar Aficionado contributing editor.

Photos by Pam Francis